Table of Contents Show

Smart land planning isn’t a buzzword; it’s a repeatable recipe backed by public-sector guidance and research. Done well, it mixes land uses, keeps daily needs within a short walk, preserves green space, and designs streets for people first—principles summarized by the U.S. EPA’s Smart Growth overview.

What “smart” really means (in plain English)

A practical lens is the well-known Smart Growth playbook—mix uses, build compactly, diversify housing and mobility, preserve open space, strengthen existing places, and collaborate transparently—outlined in the EPA’s printable Smart Growth Guide (PDF).

Streets that work for people (and businesses)

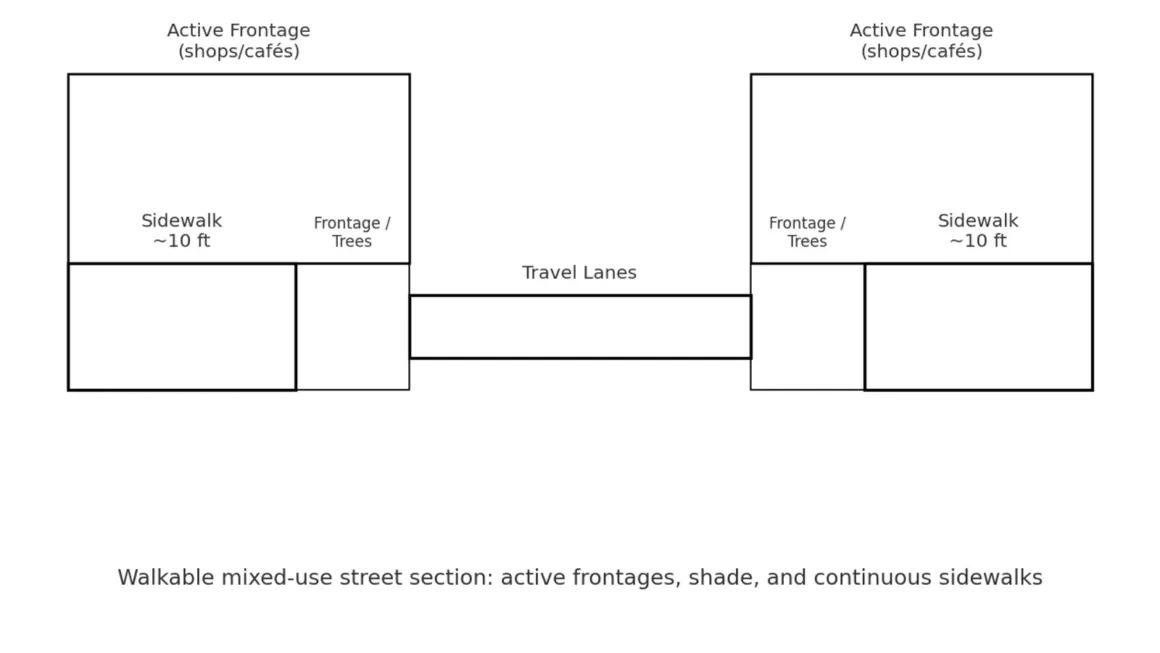

Walkable blocks are measurable, not just “nice to have.” The LEED-ND credit for Walkable Streets points to continuous sidewalks and people-first frontages; as a rule of thumb, retail/mixed blocks target ~10 ft (≈3 m) sidewalks while residential streets can be narrower. See the credit language for specifics: USGBC: Walkable streets (LEED-ND).

Green space as health infrastructure

Parks, pocket greens, and street trees function like public-health infrastructure. The World Health Organization’s evidence review links urban greenery to improved mental health and lower cardiovascular risks and mortality: WHO: Urban green spaces & health (PDF). For a mainstream, research-informed summary you can share with residents and clients, see Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: Time in nature and health.

Mixed-use & compact patterns: the traffic and emissions angle

Decades of synthesis show that compact, destination-rich patterns are associated with lower vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and reduced transport emissions, especially when paired with transit and safe walking/cycling. The canonical summary is TRB Special Report 298 from the National Academies: Driving and the Built Environment (PDF). For a policy-oriented explainer on why land use complements transit and electrification, see Urban Institute: Reducing transportation emissions through land-use policy.

Community trust is designed (not improvised)

Engagement that moves beyond “inform” to “involve” or “collaborate” builds staying power for any plan. Set expectations with the globally used IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation (PDF), and close the loop after each workshop with a “what we heard / what we changed” memo.

A quick scenario: same site, two futures

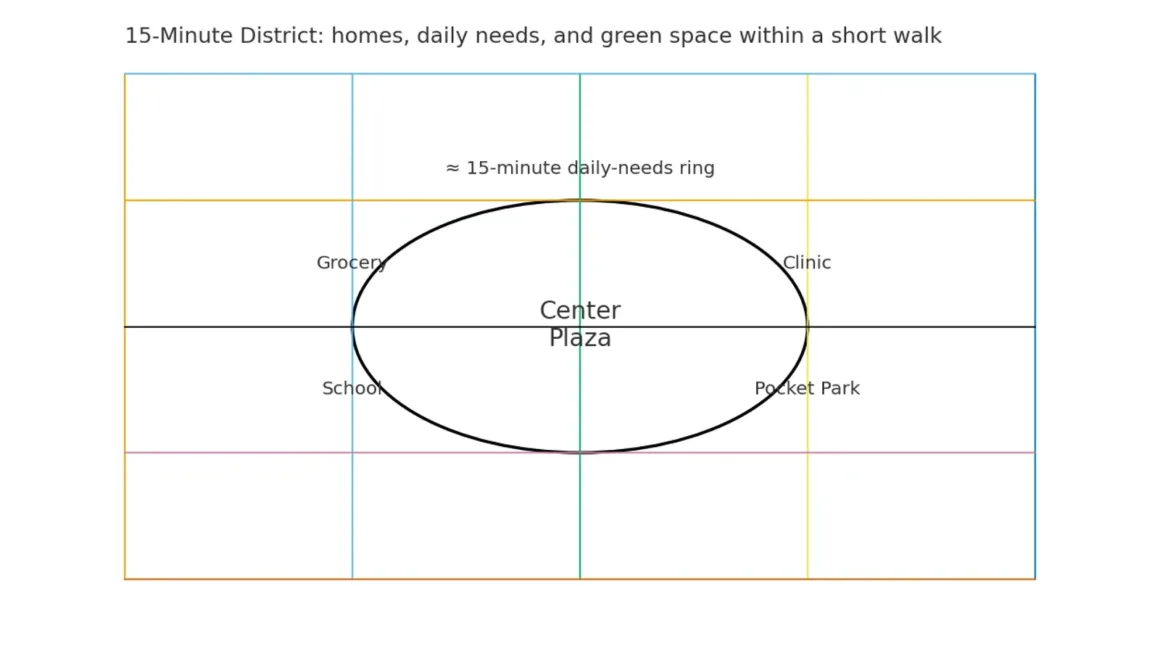

On a hypothetical 12-acre infill parcel, a single-use plan (housing only) pushes most daily trips by car; a mixed-use concept (homes over shops, daycare, a small clinic, pocket park) keeps errands within a 5–15-minute walk and enables shared trips. That pattern aligns with findings synthesized in Driving and the Built Environment and reinforced by Urban Institute’s explainer: compact, destination-rich districts tend to lower VMT and CO₂ compared with single-use sprawl (context still matters—transit, street design, pricing).

Site-level moves you can copy this week

- Frontage & shade: Continuous storefronts, trees every ~30–40 ft, and 10-ft sidewalks on mixed blocks (per LEED-ND Walkable Streets guidance).

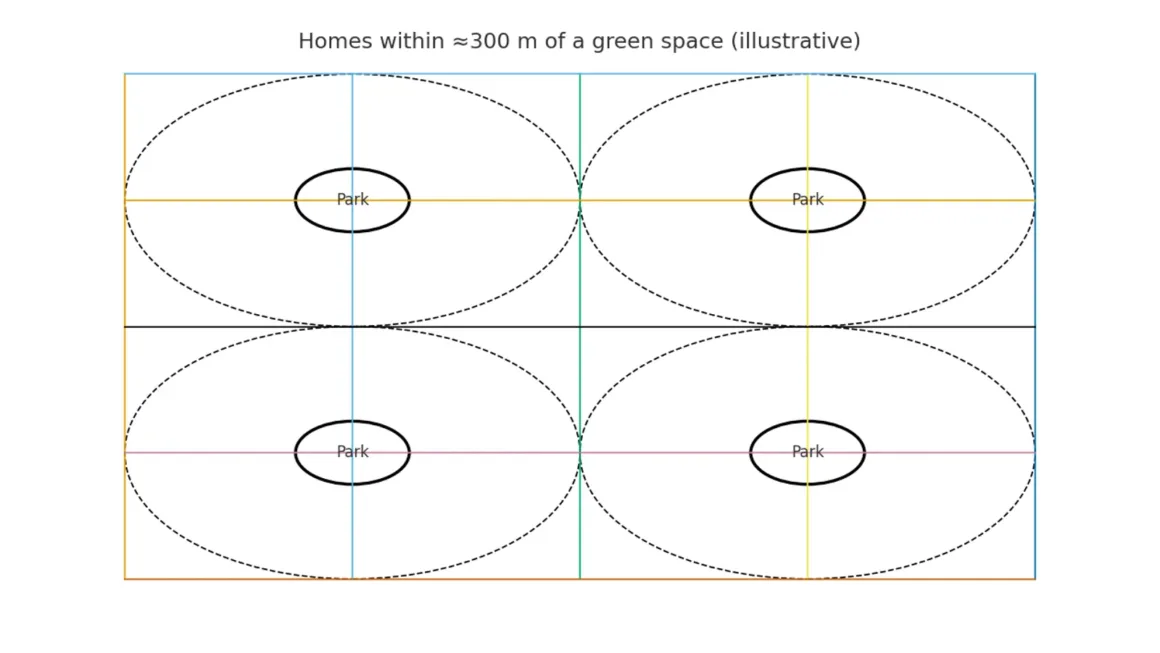

- Green rings: Aim for most homes within ~300 m of a usable green space (a sub-five-minute walk), consistent with the direction of the WHO evidence.

- Engagement promise: Publish your IAP2 level at project start and close the loop with a one-pager after each touchpoint.

Choosing a planning partner

Look for teams that cite recognized frameworks (EPA Smart Growth, LEED-ND), show measurable post-occupancy outcomes (mode share, canopy coverage, small-business survivability), and operate with a transparent engagement plan (IAP2-style).

FAQ (People Also Ask)

It’s a way of arranging homes, shops, streets, transit, and green space so most daily needs are close, routes are safe to walk or bike, and natural areas are protected.

Compact, mixed-use patterns typically shorten trip distances and make walking or transit viable—so total driving (VMT) tends to drop compared with single-use sprawl.

A practical target is about 10 ft (≈3 m) on retail/mixed-use blocks, with ≥5 ft (≈1.5 m) on quieter residential streets.

Yes. Even small, well-placed green spaces are linked with better mental wellbeing and reduced heat stress when they’re within a short, routine walk.

Land use planning sets the “what goes where” (uses, densities, mobility networks). Urban design shapes how it feels at street level (frontages, trees, lighting, sidewalks).

Track simple KPIs: % of homes within ~300 m of a park, average block length, sidewalk continuity, shade canopy, mode share, and small-business footfall.

Set expectations up front (inform/consult/involve/collaborate/empower), meet people where they are, and publish “what we heard / what we changed” after each round.

Often, yes—walkable amenities, trees, and safe streets tend to support neighborhood desirability and local business performance (context and execution matter).

No. Towns and suburbs benefit too—think connected neighborhood centers, safe crossings, shade, and small parks stitched into daily routes.

Widen and clear sidewalks on your key mixed-use block, add continuous shade trees, and align crossings to shorten pedestrian wait and walking distance.

Park access within ~300 m: 42% → 78% • Sidewalk continuity: 63% → 95% blocks • Mode share (walk/bike/transit): 18% → 32% • Small-business footfall: +21% YoY